Containment

themes of isolation throughout Eddington and 28 Years Later

Y'all are gonna be reading a LOT of analyses on films, novels, and video games over the next few weeks.

My partner (now able to move a bit more on crutches) and I finally treated ourselves to catching up on a lot of the big releases from the last month or so in theaters, and -- me being me -- I can't help but find a lot of fascinating connective tissue between each piece that says something about where we are, collectively, in this very moment.

And while I could certainly wax poetic about Fantastic Four: First Steps and how much I adored its aesthetic, its sincerity, and its unabashed view of a better and more empathetic world, I think I've gushed over recent Marvel products enough.

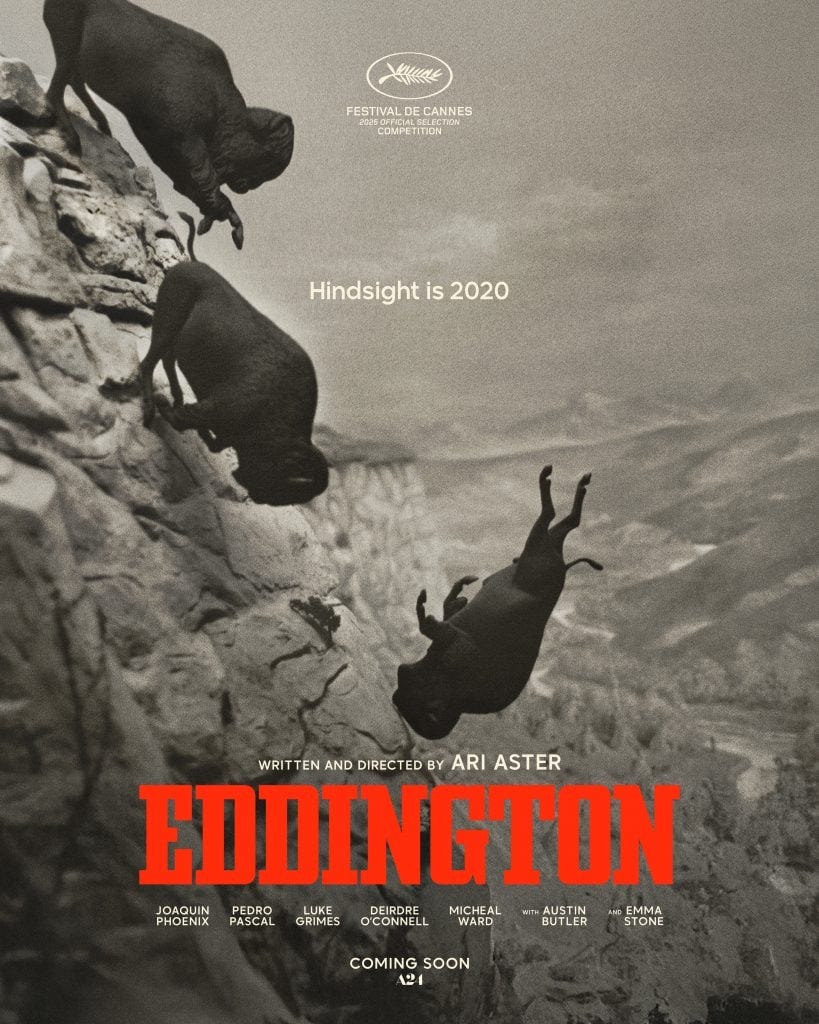

Instead, I'd like to examine the throughlines that connect two of my favorite films for 2025 -- Ari Aster's Eddington, and Danny Boyle's (and Alex Garland's) return to their esteemed zombie franchise with 28 Years Later.

Examining each independently first, it feels like Eddington is a movie that is really resonating with viewers.

A modern western told in the times of the Covid pandemic, it's a dark, hilarious, and bleak character study on how easily manipulated the American psyche can be with even the mildest of inconveniences, assumptions, misinformation, and external pressures. It's about fragility (male fragility specifically) and how quickly confusion, cowardice, and ignorance can lead to extremism.

Without getting too far into spoilers, Eddington is about the sheriff of a rural town in New Mexico, where everyone knows everyone, and the small police force are often at odds with the bordering lands owned by the native American tribes. The story kicks off in the midst of the pandemic, where everyone has annoyingly strong feelings about masks, distancing, and capacity limits. There's an upcoming election where the incumbent mayor is expected to win re-election with ease. All the news is covering a distressing uprising against police brutality in Minneapolis. Several men have accused other men of sleeping with their wives (or worse, in some instances.) Everyone knows everyone. Everyone knows everyone's kids, and generally dislikes them.

It's a Blue Velvetesque smalltown, set against the painted big skies of the southwest.

There's even a proposal for a datamining AI center to be built just on the outskirts of town, suggesting that there's a great, evil, faceless, big bad that can be felt, but never confronted directly.

When the sheriff -- whose homelife is already in shambles as his wife and her mother spiral deep into doomscrolling, conspiracy theories, and severe bouts of paranoia -- becomes convinced that the town's mayor is the source of all Eddington's covid-related stressors, he makes a bold proclamation to run as the opposition in the upcoming election.

Gunslingers at noon. Tension builds. Accusations are flung. Protests arise.

The entire first half of the film is just filling the powder keg. It's setting the stage for what we know will be an absurd, bloody, uncontrollable finale.

But the film's key aspect that ultimately guides us through every beat of the film is Isolation.

The quarantine is what kicks off the story, but its a feeling of remote loneliness that dictates every last decision made in the film. When characters are alone, they resort to their phones for comfort, and their screens only exacerbate every fear they've ever had. When they're with their wives or their children, there's an emotional distance that makes every interaction awkward and tense. When groups of people are together, there's a lack of empathy or common understanding that makes every character read as "sore thumbs" against one another, removing the ability for connection or understanding, and increasing the likelihood of confrontation.

And in that isolation is where I think Eddington really speaks to the audiences of 2025.

Even now, as we've "returned to normalcy" and are out and about, I feel as though we never really left that isolated bubble from covid. Whenever we're in a crowd now or with a group of friends, there's a distance between everyone. A sort of barrier that blocks connection, conversation, or further understanding. A chosen isolation that somehow feels safer, more comforting, and reliable than the idea of reaching out and being hurt, rejected, or misunderstood.

It stands to reason then that, by the logic of Eddington, we have spent the last 5 years relying on phones, conspiracies, news media, and paranoia to fuel most of our daily interactions. Nothing feels in our control, and no one feels trustworthy.

We’re all filling our powder kegs, and just waiting for a flame.

Meanwhile, 28 Years Later, on its surface, feels less intensely cerebral.

While it's been a long while since I've watched 28 Days Later or 28 Weeks Later, the tale of a zombie outbreak is as old as time. To my recollection, 28 Weeks Later ends with the Rage Virus spreading to mainland Europe, and the film remaining ambiguous as to whether the virus successfully consumes much of the world, or if the military forces set to firebomb Paris will successful hold back the infected.

28 Years Later answers this question pretty much immediately -- the firebombing was a success. Mainland Europe was spared much of the ravaging we might've expected after the previous film, and instead the Rage Virus was driven back to the UK, which was then immediately quarantined by the greater EU and permanently left on lockdown. In the wake of that, the body of England/Scotland has been retaken by nature and repopulated with the devolved bodies of the infected (some of which have apparently reverted into fat, sluggish, silent types, and others into 'alpha' ubermensch troglodytes.)

The story itself revolves around a small island just off the coast of England (okay, it might Scotland) where civilization has slowly been rebuilt, roughly to the time of the Dark Ages where electricity and advanced technology is still far from their grasp, and is now literally gated off and protected by the ebbing tides. A young boy comes of the age where he's ready to explore the mainland with his father -- seemingly to hunt and kill the infected, and forage for supplies. A lot of the first half of the film is simply exploring the two worlds and establishing the new rules of the post-virus UK.

Once the horror and science-fiction footwork is set up, the second half of the film makes a fascinating pivot and becomes more of a coming-of-age/family story. After making it back to the island, the boy becomes obsessed with a campfire he saw on the mainland, where the only known doctor in the entire UK resides. The only hope for the boy's mother, who has been kept locked upstairs for ages as her mind deteriorates from an unspecified disease, is to see this doctor on the mainland. Alone, the boy frees his mother from their home against the wishes of his father, and guides his mother back through the zombie-ridden mainland in hopes of a cure.

And so much of this second half of the film is built around a similar feeling of Isolation.

The first part of their foray into zombie territory is quiet. An exploration of liminal vastness that expands out from sea to sea, across empty fields and hushed greenery, which only exacerbates the hollow feeling that this promise of a doctor is folly. The boy is acting out of desperation to save his mother, and, perhaps to a greater extent, spite his father.

Once they do start encountering the infected, other characters are introduced who are certainly lively and relatable, but I'd argue their contributions only further pull the boy and his mother away from any sense of community. The sheer presence of living humans on the mainland diminishes the value of their home island -- which, last we saw, was hosting a bizarre display of regressive revelry to preemptively usher the boy’s first successful hunt. A sight he clearly rejected and felt disgust for. In essence, the boy is actually identifying with nature and the culture of the infected more than he is with any living person. Perhaps out of sympathy for his dying mother, who at one point directly connects with one of the infected on an emotional level, or perhaps out of complete disdain for his father’s animalistic behavior at the aforementioned party.

THESE opposing forces are what really got me thinking about the connection between these films.

In Eddington, the sheriff quickly abandons his sense of humanity and community in the wake of isolation, disinformation, and external pressures.

In 28 Years Later, the boy slowly abandons his humanity and community in FAVOR of isolation, quiet, and a return to natural harmony (in all its bloody, carnal chaos.)

Extremes on either end, responding to unseen, destabilizing forces, built around isolation and containment. The powder kegs filled inside each of them, that can be lit with just the right circumstances.

I think what I like most about this dichotomy is that the story about a small town in the middle of nowhere is the one that leads to absolute terror in the third act, while the one about a zombie-plagued apocalypse is the one that ends with a calm, absolving resolution that centers on making peace with death. Both play into working against their own conventions for the sake of suggesting that we may find grace in the most unlikely of places, and that the more justified we think we are, the more likely we are to descend into unmitigated rage.

Which feels more prevalent in 2025 than it even did in 2020.

The self-contained anxieties that exist within all of us, that we all suspect will be released in toxic and violent ways if and when our situations start to feel untenable. The yearning to up and leave everything behind and return to an empty field of open space -- even if it means having to fend for ourselves against the elements.

There's a less than subliminal message in both films that suggests the end of the world as we know it is happening right now -- and I'm not just referring to the apocalyptic futuristic setting. Both films spell the death of humanity, at least as we currently understand it.

Both Eddington and 28 Years Later are less than subtle in their notion that the main characters DO NOT LIKE where their world is at, and where it's heading. They see no way out of their current predicaments -- as the township of Eddington is heading towards an inescapable timeline where masks, protests, social distancing, and white guilt are the new norm -- and the small island off the coast of England (Scotland, whatever) remains in a perpetual cycle of medieval standards, laced with endless justifications for heavy drinking and brutish promiscuity at the expense of those suffering without access to modern medicine or technology.

And isn't that 2025 in a nutshell? To constantly have anger, bottled up inside of us. A rage for the world we're trapped in -- unsure of who to trust, but positive we're not happy with where we're heading. To resent those who are attempting to make light of the moment, and to actively work against those we think are perpetuating its hierarchy. An irresistible urge to either lash out, or to just run away from it all.

A desire to break quarantine. To breach containment.